For most people, venturing 3,000 feet underground, weaving in and out of tight fissures and not seeing sunlight for days at a time is a nightmare. Heck, some people don’t even like to explore caves in Minecraft. But for a cave explorer, also called a caver, the idea is exhilarating. Whether you cower at the thought of touring a cave or whether you’d jump at the opportunity, caves remain an important and vastly untapped wealth of knowledge and beauty.

The key to understanding the importance of cave exploration is first understanding karst. Karst is a type of topography composed of soluble carbonate rocks, like limestone, and it forms a rough landscape full of ridges, caves, sinkholes and other formations. Since they tend to have underground pockets that allow groundwater to collect and even flow through subterranean rivers, karst landscapes provide natural drainage systems.

According to the British Cave Research Association, 678 million people worldwide “rely on this karst groundwater.” In general, groundwater and aquifers sustain surface-level bodies of water like lakes and rivers, a lot of which are found in karst areas. If we want to prevent the contamination of these water sources, scientists need to understand karst topography. This can partly be accomplished through cave exploration.

On top of that, caves have the potential to house life that is unheard of on the surface of the Earth. On its website, Canadian Geographic describes the “ancient ecosystem” of the Castleguard Cave in Alberta, Canada. An aquatic crustacean, Stygobromus canadensis, isn’t found anywhere else on Earth and occupies the “puddles and streams” of the cave.

And while natural beauties like valleys and glades tend to steal the spotlight, caverns full of crystals have their own beauty. For example, the Pulpi Geode in Spain has been dazzling visitors with its transparent crystal walls for the past 20 years. To learn more about these rare ecosystems and brilliant wonders, we need cave exploration.

Karst landscapes also tend to contain valuable minerals, fossil fuels and rocks commonly used throughout society. Though all rock foundations have the potential for developing geohazards like sinkholes, karst landscapes are particularly prone to it. Local karst topography needs to be studied, so people can not only successfully mine but also avoid certain dangers.

But sinkholes aren’t the only dangers associated with caves. Many risks come with cave exploration, so while I advocate for the importance of it, I also advocate for cave safety.

According to saveyourcaves.org, the most common dangers to cave explorers are “falling, being struck by falling objects and hypothermia,” but others include getting lost, running out of light, passages flooding and injury. In order to reduce caving accidents, the caver should always be prepared. The Southeastern Cave Conservancy (SCCi) suggests packing a reliable source of light, a helmet to protect against falling rocks, food, water, basic medical supplies and proper clothing to protect against the cold.

The SCCi recommends caving in groups of four. This way, if someone is injured, one person can stay behind, and the others can fetch help. It is also helpful if at least one person in the group knows the cave well and has significant experience in caving. At the very least, the most important rule to follow is to never cave alone.

So, whether you cave for fun or for science — or whether you’d rather sit this one out — cave exploration, though not without its risks, can introduce hidden worlds like you’ve never seen before.

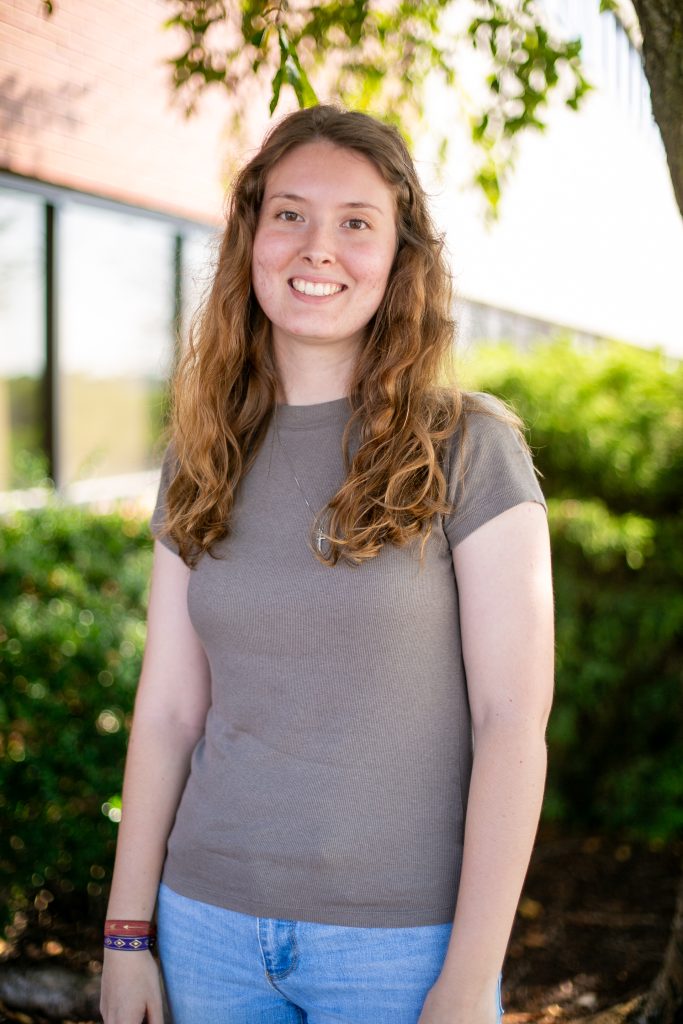

Bear is the feature editor for the Liberty Champion. Follow her on X