Biology Department Provides Students Unique CSER Opportunity Through Taxidermy

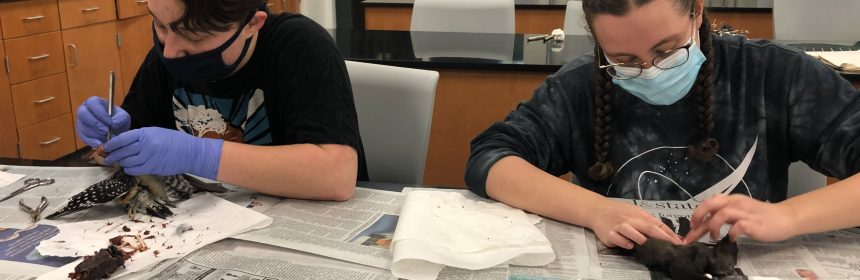

It is 5:30 on a Tuesday night and five students and a professor just arrived at a classroom in the Center for Natural Sciences. The students prepare their stations, covering the black lab bench tops with newspapers and laying out a pair of scissors, forceps, scalpel, probe, beaker of water and container of cornmeal. Then, they head over to the large freezers on the side of classroom, take out bundles wrapped in paper towels and sit down to start work for the next two hours.

“This is the best CSER I’ve found so far,” Kaelyn Long, a forensic science and zoology double major, said. “I love telling people, ‘Oh yeah, my CSER is bird stuffing.’”

Since 1997, Dr. Gene Sattler, professor in the biology department, has amassed a collection of over 1,000 birds stored in freezers in the biology department. Sattler has salvage permits through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services and the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries. These permits allow Sattler to salvage dead birds, which he finds himself or Lynchburg Bird Club members, Liberty faculty, bird rehab centers or others who hear about his work save for him.

Sattler and his students have stuffed over 300 specimens, ranging from hummingbirds and woodpeckers to great horned owls and endangered whooping cranes.

“In addition to adding to our collection, it really gives the students more knowledge of animal anatomy and improves their dissecting skills,” Sattler said.

Students, who receive Christian service hours for their work, handle the birds from start to finish. The process takes students seven to eight hours to complete per bird.

When students receive a new specimen, the first step is to make a cut through the skin along the bird’s keel, the midline of its chest where no feathers grow. Careful not to cut into the muscles below or rip the skin, this incision allows the students to peel back the skin and work through the long and tedious process of removing all organs, muscles, tendons and tissues from inside the bird. Anything besides skin and some bones left inside the bird may cause it to rot and smell.

Once everything is cleared out, students tie the shoulders together inside the bird and, in place of the backbone, insert a wooden stick down the middle to keep the bird stable. Then they stuff the bird with rolled cotton in smaller birds and excelsior softwood shavings in larger birds and sew up the midline.

Then they prepare the bird for drying, tying the legs to the wooden stick and the beak shut, and lay the bird prostrate on a foam board with wings folded against the body and pinned to keep it in place. Once the bird dries, they will not be able to adjust its position, so they make sure feathers are lying naturally and flat.

Unlike taxidermic specimens, which have wires inside to hold the animal in a certain position and are meant for display, these scientific specimens are used primarily for research and education. Scientific specimens are positioned to save space in storage cabinets and protect the birds from damage.

“When you go to the Smithsonian, they do have exhibits where they have mounted specimens, but that represents 0.1% of what they have, and 99.9% are specimens prepared like this for scientific use,” Sattler said. “If somebody’s studying the species and looking at geographic variation across the country in size and color, they can go to museums all around the country and get permission to look at their specimens.”

Once the birds have dried, they join the collection of animals, which also includes fish, reptiles and amphibians preserved in alcohol and taxidermic mammals like skunks, porcupines and flying squirrels. Sattler uses the collection mainly for educational purposes in classes like vertebrate natural history and ornithology and at talks for local Boy Scout troops as well as the Virginia Master Naturalist program.

“I’ll bring out these trays and trays of specimens, and we’ll see really close, in hand what all these birds look like and subtle differences between the sexes,” Sattler said.

As the students finish up work on Tuesday nights, they return their birds to the freezer or leave the specimens on foam blocks to dry. These students have played a part in giving these birds new life both in form and in giving other students hands-on access to wildlife specimens.

Jacqueline Hale is the Feature Editor. Follow her on Twitter at @HaleJacquelineR.